Robots and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are key parts of the Fourth Industrial Revolution, and every business will use them (eventually). Humans and robots will work together seamlessly in different industry sectors. Salesforce is pioneering this new age with the Lightning Platform by bringing together all of the important things in a business — customers, partners, employees, and robots.

Once upon a TrailheaDX, a group of fearless Trailblazers met to embark on a robotics journey. It all started with a crazy idea: Why don’t we build a demo with robots? This proposition kickstarted an intense brainstorming in which even crazier ideas were proposed. We came up with concepts like a robot race, fighting robots…We almost started our own Skynet but rest assured, we settled with a more reasonable idea in the end: we chose to simulate a robotic supply chain with AI-driven quality assurance.

Our demonstration illustrates how the Salesforce Platform can integrate very different systems with the combined use of Lightning, Platform Events, and Process Builder. This is the story of what we built, how we did it, and the challenges we faced.

Meet the robots

Our scenario involves three different robots: an ARM, a Linear Robot and a YuMi. These robots work together in this exact order to select and ship supplies.

ARM

The ARM is a robotic arm mounted on a tripod. It is built by GearWurx, a small company based in Utah. It has six degrees of freedom (joints) and can carry up to ten pounds (4.5 kg). It rotates on its base at almost 315 degrees and has a reach of 7.2 feet (2.2 m) of diameter.

The ARM can be manually controlled via a controller fitted with six sliders or via software with a Pololu Maestro servo-controller. In the context of this project, we chose to automate the ARM and augment it by attaching a Raspberry Pi with a camera on top of it.

Linear robot

The linear robot is a belt-driven conveyor system that we built just for TrailheaDX. It is controlled by a Raspberry Pi. The main body is built using v-slot aluminum beams from OpenBuild, and the basic pattern is modeled off of the OpenBuild Linear Actuator kit. The belt is driven by a NEMA 17 stepper motor that is controlled by a Pi-Plate Motor Plate attached to the Raspberry Pi.

YuMi

The last robot that operates on the supply chain is YuMi from our great customer ABB. As you may have guessed its name stands for “you and me.” It is a dynamic cobot — a robot that is meant to safely operate along with a human.

YuMi is very different from our other robots. It is an industrial-grade robot that is fitted with collision sensors that makes it stop instantly if it hits anything. It has two arms with seven degrees of freedom in each arm and it is extremely accurate — to the point where it can even fold paper planes!

For the needs of our demo, we have augmented YuMi by adding two cameras on top of its “head.”

How the magic unfolds

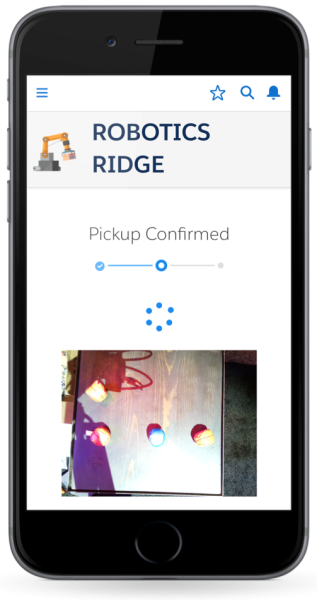

Our demo scenario starts with a user selecting a type of payload to be shipped via a Salesforce Mobile app built with custom Lightning components. The app allows the user to select one out of three types of payloads: a soccer ball, a basketball, or a globe.

Once the user requests a shipment, the mobile app fires a platform event.

Platform Events are part of Salesforce’s enterprise messaging platform. The platform provides an event-driven push messaging architecture that enables apps to communicate inside and outside of Salesforce in near real-time. This facilitates integration with third-party applications. You can learn more about Platform Events on Trailhead with this module and this project.

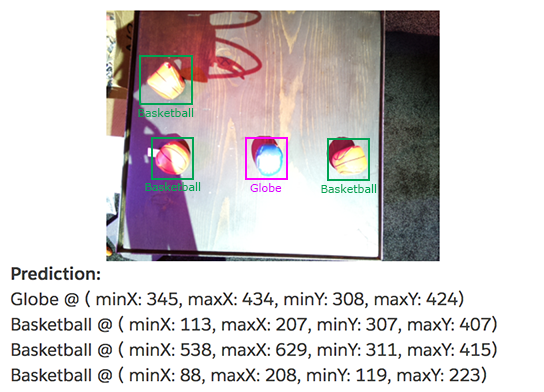

Upon receiving the platform event, the ARM rotates, places itself over the pickup zone, and captures a picture. It uploads the pictures to the Salesforce Platform via a custom REST API. The upload triggers a process built declaratively with Process Builder. The process runs Einstein Object Detection on the captured image. Einstein predicts what kind of items are on the table and where they are.

Once the objects are detected, the platform fires a platform event to instruct the ARM to pick the appropriate object. The ARM grabs the objects, moves it to the linear robot, then fires another platform event to notify that it has dropped the payload.

The linear robot moves the payload next to the YuMi and fires a platform event to notify that it has delivered the payload.

YuMi picks the payload, places it in front of its camera, and captures a picture for inspection. It uploads the pictures to the Salesforce Platform via a custom REST API. The upload then triggers a process which runs Einstein Image Classification. Einstein predicts what kind of payload is on the picture. We then use the prediction result to perform quality assurance by validating whether the payload type matches the one that was initially ordered by the user.

After running quality assurance, the platform fires a final platform event with the test result. YuMi drops the payload with a specific gesture based on the test result.

See the robots in action in this video.

Near real-time monitoring

Along with the execution of our demo flow, we implemented three tools that would help us to monitor and showcase progress in near real-time.

Salesforce Mobile app

The mobile app that triggers the shipment is also listening to Platform Events. It tracks the progress of the delivery and displays the picture captured by ARM before the pickup.

Lightning app

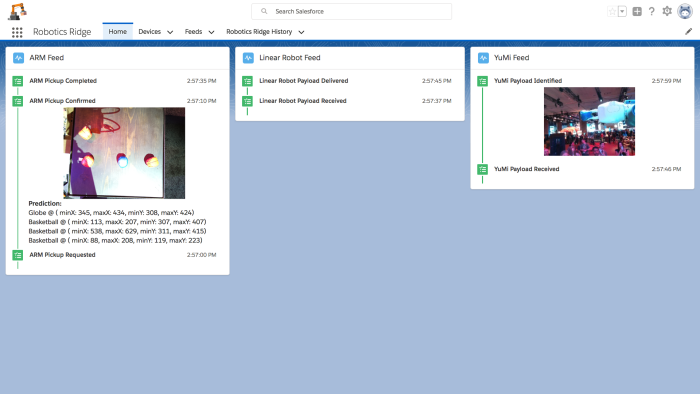

Along with the mobile app, we created a Robotics Ridge Lightning app that would continuously display the current status of the supply chain.

This app uses three instances of a custom configurable Lightning component. The Lightning component displays a feed that matches the activity of a given robot. The feed is automatically updated as the component receives Platform Events.

IoT Explorer

On top of these two tools that were developed with custom code, we also leveraged a declarative approach by using the IoT Explorer. Learn more about the IoT Explorer with this short Trailhead project.

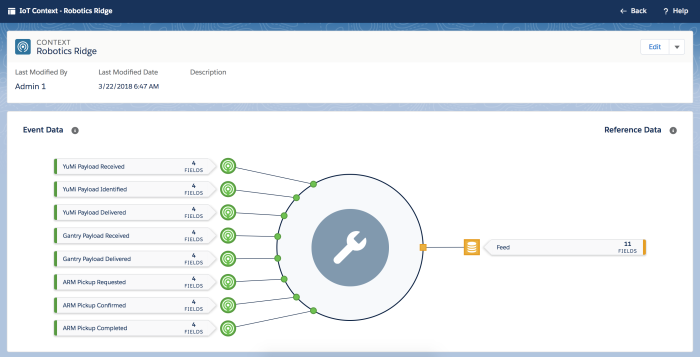

We started by defining a context for our orchestration. The context defines the inputs that will affect our orchestration. In our case we had eight Platform Events for the different actions that the robots performed and the feedback they sent (e.g. ARM pickup requested, YuMi payload delivered). Each platform event contains an ID mapped to a feed record.

Because we ran the same demo in parallel on the two ends of our booth, we needed to be able to discriminate the incoming Platform Events (i.e. whether it is the ARM on the right or left picking up a payload). The feed ID is a unique identifier that allows us to track our two demos in parallel.

Then we configured an IoT orchestration based on this context. We set up a list of states that were pretty identical to the list of Platform Events and we defined transition rules. The transition rules defined how the orchestration would move from one state to the other (by receiving the right platform event).

This was a simple configuration achieved with clicks only. It provided us with another form of monitoring of our demo. We could have gone further and use the IoT orchestration to control the robots but we stuck with a read-only display.

Challenges and lessons learned

Integrating multiple environment stacks

One of the main challenges with this project was the integration all of the different environments. Because we were running with different physical devices (a mobile app, a laptop, three types of robots), we did not have the luxury of adopting a unified technology stack.

We were limited by time, so we had to use existing libraries to control the different robots and this led to a complex mix of technology:

- The ARM is controlled by a Raspberry Pi running a Node.js app.

- The Linear Robot is controlled by a Raspberry Pi running on Python.

- The YuMi is controlled by a laptop running a C# app.

Platform Events proved to be a life-saver when integrating these different stacks because we were able to push information to all devices in near real-time.

The use of Platform Events was also very beneficial during the development phase thanks to the decoupling it introduced. We tested parts of our flow independently by firing test events from bash scripts. The scripts called Salesforce CLI to execute anonymous Apex and fire the events.

Einstein Object Detection training

Part of our demo relies on Einstein Object Detection to predict the type and position of the items that the ARM will pick up.

While Einstein Image Classification is quick to train and requires limited efforts (See it for yourself in this Trailhead project), Einstein Object Detection training is more time consuming.

Einstein Image Classification and Einstein Object Detection are two artificial intelligence services that are part of Salesforce Einstein Vision. Einstein Image Classification predicts an image and classifies it into a specific category (i.e. Is it a mountain? Is it a beach?). Einstein Object Detection predicts where certain objects are on a picture (i.e. How many cars are on this picture and where are they?).

Einstein Object Detection requires more sample data than Einstein Image Classification. We need to capture pictures of the objects from various angles to increase prediction reliability.

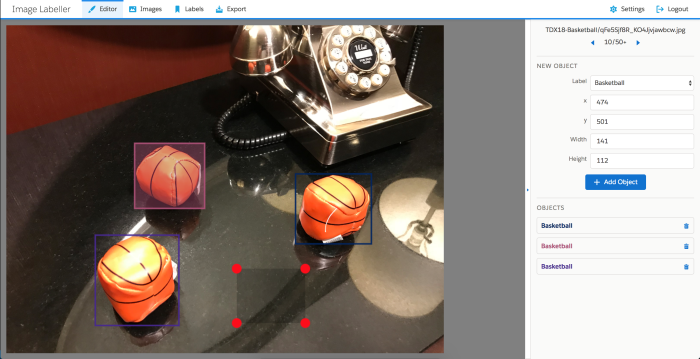

Einstein Object Detection also requires a lot of manual operations as each object in pictures that compose the model must be manually tagged with a box. This process is rather long so using a dedicated tool greatly helps. There is a paid for partner app available on the AppExchange and you can also use tools that are not Salesforce specific (Although you would have to reformat the output to match the Einstein API format).

In the context of this project, we used a tool creatively named Image Labeler which I am developing. I started working on that as a side project a couple of months ago and it is still a work-in-progress (Functional but not secure) so it is not publicly available yet. I plan to contribute it as open source in the upcoming weeks. It is a Node.js/React app that runs on Heroku. It uses Cloudinary (An online image hosting service) to store pictures and PostgreSQL database to store object tags. Once images are uploaded and tagged, it generates a ZIP file that is compatible with Einstein Object Detection APIs.

It was the first time that we (The project team) used Einstein Object Detection in a production-grade project so there were some unknowns about the level of effort required to obtain reliable predictions for our three payload types.

We ended up spending about a day to capture nearly 500 pictures with our phones and tag 700 objects. This gave us quite accurate results in a test environment.

However, things got more complicated when we moved into the conference venue. The strong and colored lightning of our booth altered the pictures we took and this degraded Einstein’s predictions. We could have mitigated this issue by retraining our model with some extra pictures taken on site but we were too short on time.

Here are some tips for you if you plan to train an object detection model:

- Capture at least a hundred pictures per object in your model.

- Take pictures from various angles, with different backgrounds and lighting conditions.

- Save some time by taking pictures with multiple objects in them (Unless you plan to reuse the same images in an image classification model, which we did).

- Use a tool to tag the pictures.

Synchronizing the robots

Another obstacle on our project path was the fact that the robots were owned by three teams based in different locations: one in France, one in Colorado, and the last one in California. This meant that we could only test the full demo flow when we all met, and that was just days before TrailheaDX! This left us very little runway to make last-minute changes.

We took some precautions ahead of time, but one of the things that surprised us was the fact that the two ARMs were not physically configured in the same way. Their servomotors’ “home” position turned out to be different so we had to calibrate the two ARMs separately. A direct consequence of that is that the series of commands we issued for one would not work for the other one.

We ended up losing precious time to fine-tune their positions. The only way to avoid that would have been to test on the two physical devices from the start. Unfortunately this was not an option for us.

Once we compensated for that, we ran a long series of tests to simulate the full demo flow and check that it could run reliably over time. This try/fail approach is very different from the way we should test software, but it was a necessary evil in this context. In the end these physical tests proved valuable as we did not face any major problems during the show.

Closing words

Despite last-minute surprises, we were able to deliver one of the most innovative demos presented at a Salesforce event, thanks to the dedication and efforts of the Robotics Ridge team through a month-long journey.

Now is the time to embrace the Fourth Industrial Revolution with the Salesforce Platform. Play your part by creating custom user experience with the Lightning Component Framework. Integrate with multiple environments with Platform Events. Create complex processes with clicks using Process Builder. Control swarm of devices with IoT Explorer and augment their intelligence with Einstein services.

Resources

Learn more about the cool Salesforce Platform features used in the Robotics Ridge on Trailhead:

About the author

Philippe Ozil is a Senior Developer Evangelist at Salesforce where he focuses on the Salesforce Platform. He writes technical content and speaks frequently at conferences. He is a full stack developer and a VR expert. Prior to joining Salesforce, he worked as a developer and consultant in the Business Process Management (BPM) space. Follow him on Twitter @PhilippeOzil or check his GitHub projects @pozil.